Molting often comes as a surprise to newer chicken owners. It is not always noticed until the second year of life with a flock because of the age at which it happens. So as a relatively new but not brand-new chicken keeper, it can take you a bit unawares.

One day you go out and start noticing more feathers around the coop than normal. You start noticing a dip in egg production. Soon, the whole place looks like a pillow fight went on in the night. You start thinking something isn’t right.

But that’s not true. If it’s fall and your chickens are over a year old, everything is right. Your chickens are going through a completely natural and necessary process called molting.

Jump to:

- When Does Chicken Molting Occur?

- At What Age Does Chicken Molting Happen?

- Youth and Juvenile Molting in Chickens

- Molting in Adult Chickens

- Molting at Other Times of Year

- Signs of Chicken Molting

- Managing Molting in Chickens

- How Long Does Chicken Molting Last?

- Effects of Molting on Egg Production

- Managing Egg Production During Molting

- Tips for Bringing Chickens Back Out of Molting and Back to Egg Production

What is Molting in Chickens?

Molting is simply the process by which chickens replace their old feathers with new ones. It’s not a lot different than how your body sheds old, dead, and dying skin cells and replaces them with new ones. Considered this way, molting sounds a lot less scary, doesn’t it?

Chickens molt because natural processes like time, weather, preening and cleaning, flapping, flying, and pecking wear feathers down after a while. When feathers become time-worn, they lose their function. Some of those functions are the ability to fly up to roost or evade predators, the ability to attract a mate, and, very importantly, the ability to interlace and insulate the chicken’s body—very important in the cooling months of autumn heading into the winter.

Chickens need to shed their old feathers so that new feathers can grow from those follicles. The process starts at the head and neck and moves down and across the body until, finally, the tail feathers are lost and then replaced.

When Does Chicken Molting Occur?

Molting is triggered by signals from nature. It happens in the autumn in preparation for cold winter weather—so that those new, more insulating feathers are ready for the cold days and nights.

Shortened day length and reduced natural light are the primary triggers. The chickens instinctually know that this means a change of seasons, and the shortening days of autumn signal their bodies to molt and replace their feathers.

This is molting as it applies to older chickens in an annual molt. Age is a factor in the process, too, and molting does occur at a couple of other times in a chicken’s life.

At What Age Does Chicken Molting Happen?

Molting, in general, is a process of feather growth. When most people talk about molting in chickens, they are talking about the annual autumn molt that leaves you eggless (we’ll get to why that is in a little bit). But molting does occur at other times in the lives of chicks and chickens. Let’s talk about the different times you can expect molting to occur.

Youth and Juvenile Molting in Chickens

Chicks and young chickens will molt to replace the down they are born with and to grow adult feathers.

The first molt will occur when the chicks are about one week old (molting ages can vary a bit by breed—for example, fast-growing meat birds may molt earlier and less completely than egg-laying birds). The first molt will be complete by about one month of age, at which time you will notice your chicks are now completely feathered-out in a sort of muted mini-version of their adult selves.

The second molt will occur between two and three months old. This molt will grow feathers more in line with the chickens’ adult size, shape, and color. Roosters will grow more ornamental tail feathers during this molt, and it will become much more obvious what the sex of your chickens are. The chickens will keep these feathers until their first adult annual molt, which takes place in sync with the seasons of Mother Nature as described above.

Molting in Adult Chickens

Young chickens will experience their first adult molting cycle at around 16 to 18 months old (assuming they were born in the spring, which is the normal time for chicks to hatch). Of course, laying hens will lay at a much younger age than this, typically between four and six months old. That means that in their first year, spring-born chickens will not go through a fall molt and will not lack in egg production. You won’t see that as a notable issue until your birds’ second year.

In your chickens’ second adult year, at about one and a half years old, your chickens will need to replace their feathers, and they will molt in the fall when the days begin to shorten.

Molting at Other Times of Year

It is possible to see your chickens molt at other times in their lives. Some chickens will go through a fairly quick molt in the spring, which may not be a complete molt. It is not uncommon for chickens to molt after they have sat on a nest or hatched a clutch of eggs.

Some chickens molt at odd times just because they are odd birds, but in general, if you see your chickens molting at other abnormal times of the year, you should be looking for more serious causes. Chickens can molt due to stress to replace feathers lost to pecking by other flock-mates as a result of malnutrition or lack of feed, lack of adequate access to water, lice, or parasites.

A common source of stress that can cause off-schedule molting and dropped or stopped egg production is attack or stress from predators. This should be one of the first things you look for and needs immediate attention.

Signs of Chicken Molting

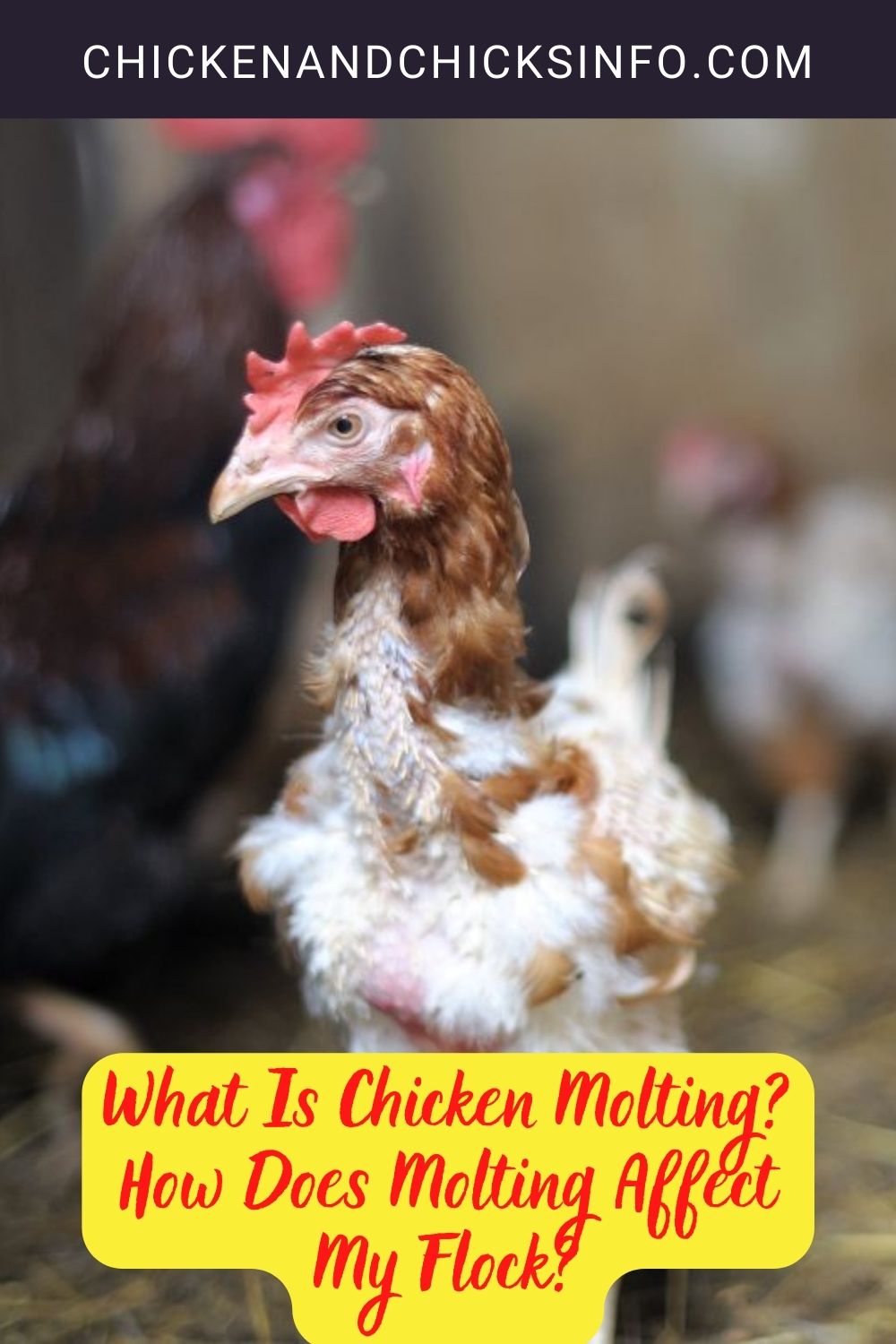

There are some tell-tale signs of molting in chickens. Once you experience a molt, you’ll know exactly what you are looking at when you go through it again. Some of the more obvious signs include:

- Reduced egg production or no production at all

- Dull-looking feathers—usually noticed right before molting starts

- Ragged appearance

- Large bare patches of skin

- Dull-looking combs and wattles

- High volume of feathers shed in the coop and yard

- Changes in chicken temperament—chickens may be more shy and hide more as they don’t want to be touched or bothered. They may also be more skittish or aggressive in a bid to warn you and others off.

- Loss of feathers on the head and neck, then moving to other parts of the body

- Feathers of different lengths with some short, new pin feathers growing in

- Increase in dandruff or dander in the coop and yard

- Waxy, white detritus in the coop area (sloughed off as new feathers come in)

Managing Molting in Chickens

Molting is a natural process, and with good regular care and feeding—not different from your normal routine—chickens will come through molting just fine and eventually return to egg-laying. There are some things you can do to help ease this process and perhaps even speed it up a bit. There are also some things worth knowing so that you don’t make this time more painful or stressful than it needs to be.

A couple of top things to note—skin sensitivity and soreness are common for molting chickens. This is because the process of breaking through new feathers makes the chickens’ skin and body more sensitive. They can become sore when touched or handled.

Also, the new pin feathers are fed by a blood-filled vein. If broken, this can cause a lot of bleeding. It is generally not harmful, but if bleeding occurs, it is a good idea to treat the broken shaft and bleeding with a product like Blu-Kote (TM). Blu-Kote will help hide the bleeding from flock-mates so they don’t target and peck that chicken and will also help prevent infection.

Other tips to help manage your flock with as little stress as possible during molting are:

- Continue to feed and water regularly.

- Limit changes to the flock or environment. This is not a good time to move coops or introduce new flock-mates.

- Limit touching and handling to limit pain and discomfort.

- Provide good, high-quality, high-protein feed or supplement your regular feed to increase protein levels (see more in the “Tips” section below).

- Reduce stress by eliminating as many stress factors as possible.

- Watch for signs of pecking and injury from other chickens in the flock. Once the flock senses weakness or starts to pick at an individual bird, they are likely to keep at it.

- If pecking is a problem, placing a red light (such as a colored light bulb or red heat lamp bulb) in the coop can help conceal the blood and help put a stop to targeting and pecking.

How Long Does Chicken Molting Last?

The average molt takes about two months to complete. There is a wide range of molting time, though, and it can take chickens as little as four weeks to molt or as long as three or four months.

How long molting lasts varies based on a few factors.

Weather severity is one of them. If you live in a very cold climate or if you are experiencing a particularly harsh winter, your chickens may not come back from molting as quickly as they would in a warmer area or in a warmer year. The reason is that they are using their feed energy more for warmth and bodily processes.

There isn’t necessarily a lot you can do about the weather, but you can at least know that there may be a reason your chickens did not “bounce back” as quickly as you expected them to.

Day length is another factor, so where you live can determine the length of time for molting in your chickens. Just like reduced daylight triggers molting and lower egg production, longer days will signal them to come back and start laying again (because in nature, longer days mean spring is coming and spring is the time of year chickens naturally want to hatch new chicks—thus, lay more eggs!).

The age of your chicken(s) will affect the length of molting. Older birds tend to take longer to molt and take longer to lay eggs again after molting. This is not surprising, as egg production tends to slow as chickens age. And again, molting takes a lot out of the chicken, rerouting and using the nutritional resources it has.

Another quite significant factor worth noting is the breed of chickens that you keep. Chickens that are bred or known specifically for egg production will usually molt faster and return to egg-laying faster than heritage breeds or dual-purpose breeds. Often these are hybrid chicken breeds like the Red Star breed that has been selectively bred for high egg production. Leghorns are another chicken known for high production and for their usefulness in creating cross-breed egg producers and sex-link birds.

Health, stress, and predation are factors, too. The less stressed and healthier a chicken is, the better its ability to complete the molting cycle. Things like harassment from dogs or targeting from predators is a cause of stress in chickens.

Effects of Molting on Egg Production

One of the more noticeable things about molting season is reduced egg production, potentially (and not unusually) down to nothing.

The energy and protein demands of molting on the chicken are to blame. They simply need to use their nutritional and energy resources for new feather production. Feathers are about 85% protein, so you can see how growing a whole body of new feathers and trying to lay protein-rich eggs at the same time can just be too much.

Instead, the body puts those resources into growing that protective, insulating covering of feathers. When the chicken no longer needs the resources for feather production, the chicken will return its feed energy to egg production.

Managing Egg Production During Molting

You can't really make a molting chicken lay, but there are some things you can do to help your chickens move through the molting process more easily, which in turn should help them return to egg laying in a timely manner. There are also things you can do to keep a steady egg flow via flock management.

One way to do this is to add new young first-year pullets that will come of laying age in the fall. Try to time age and raising so that these youngsters hit their estimated laying age in August or September. That way, when your older birds stop laying, these girls should start. This is often done in commercial laying flocks so that there is no stoppage in the egg supply.

The downfall to adding young pullets is flock size. Unless you process or cull out old birds when they go to molt, if you add new pullets every year, you will eventually end up with a large flock and will probably be feeding more chickens than you need. This might be something to do every couple of years to keep your flock young and productive, but it may not be the right answer for every year.

Of course, you can consider processing some or all of your older birds in the flock as stewing hens and replacing them all with young, fresh hens in the early autumn. Commercial flocks generally cull the entire flock in the fall and bring in a whole new flock of juvenile birds that are ready to lay. You could adopt that flock management practice if you are not one to get too attached to your chickens.

Another option is to prepare ahead of time by saving eggs, storing, or preserving the extra eggs you have in the late summer. Eggs can be stored in cold storage for at least three to four months (some sources say longer). There are other methods of storing and preserving eggs, too. If you can store enough eggs to get you through the three months of molting, it may not be a problem for you to have no fresh eggs to collect while the chickens are in molt.

Breed selection can also help you manage your flock with an eye to molting and restoring egg production. As mentioned above, the chickens bred for higher egg production usually come through molting faster, which means that they will return to egg-laying faster. Some breeds may not stop laying completely during molting. So, one way to manage your egg supply may start in the year before your chickens molt—when you choose the kinds of chickens you want to keep.

Tips for Bringing Chickens Back Out of Molting and Back to Egg Production

As mentioned a few times, you can’t really force the molting process, but you can tip the scales in your favor for a faster molt and a faster return to good egg production. A lot relies on feed management and giving your chickens plenty of protein so they can quickly grow those protein-rich feathers. Other techniques sort of replicate the signals in nature that tell chickens to start laying again. Here are some tips:

- Limit lower-protein scratch feeds, snacks, and foods

- Feed a higher protein feed. Depending on availability and your feed company, some will offer a higher protein grower or layer feed in your normal feed with a higher level of protein. Others will have a specialty feed designed for “stage of life” use like molting.

Chick grower and meat bird feeds will be higher in protein, so you can feed these or mix your normal layer feed with these feeds. Ask your feed supplier what the options are. Normal chicken feeds are 16 to 18 percent protein. During molting, try to get at least an 18% protein feed. A feed with protein in the range of 20 to 22% is even better. It will probably cost a bit more for a higher protein feed, but the cost will even out if you can bring your chickens back from molting faster and return to good levels of egg production. - Supplement your chicken’s feed with high-protein sources. Some chicken-friendly options include mealworms, hard-boiled eggs, scrap meat from kitchen and meal scraps, black oil sunflower seeds (BOSS), and cat food. This is especially helpful if your feed supplier does not offer a higher-level protein feed.

- Be sure your chickens have access to fresh, open, unfrozen water as much as possible. Good food and protein intake is key to a return to egg laying, and animals tend to eat less if they can’t drink as much water as they like.

- Increase the light in the chicken coop by leaving a light on for a few extra hours each day. You can set the light on a timer to come on two or three hours before daylight. It is recommended that light be added in the morning before sunrise, if possible, instead of at night. This is so that your chickens will maintain a natural homing and roosting cycle. Aim for a total of 14 to 16 hours of light between daylight and your supplemental light.

When molting is complete, your chickens should be returned to a regular layer ration without a lot of added protein. When chickens are not molting, too much protein can cause digestive issues. It’s costly, unneeded, and unwise.

Good general flock management will bring you and your birds through molting without a chicken scratch. Don’t fear this natural process. Your birds will know what to do. All that you need to do is give them the care and time they need to do it. Then you’ll be back in the egg business once again!